Sound hooves are the result of many things. Age, breed, metabolic rate, environmental moisture, illness, shoeing and exercise all influence horse hoof health, and the most important factor may simply be genetics. While the intricacies of the equine foot are clearly multifactorial, one thing is certain: the quality of the hoof always has a nutritional component. Inadequate nutrition can be the difference between having the potential for a hoof problem and actually developing one. Providing the dietary nourishment that the hoof needs can optimize health and provide the essentials needed to reach its potential. Because the hoof is in a continuous state of growth, dietary changes can positively or negatively affect its overall integrity. A balanced, forage-based diet is the foundation for all areas of equine health, and the hoof is no exception. Horses on well-balanced diets are much less likely to have foot problems. The balance of vitamins and minerals, the balance of net calories, the balance of activity level and the stage of life of the individual animal makes nutrition as much of an art as it is a science.

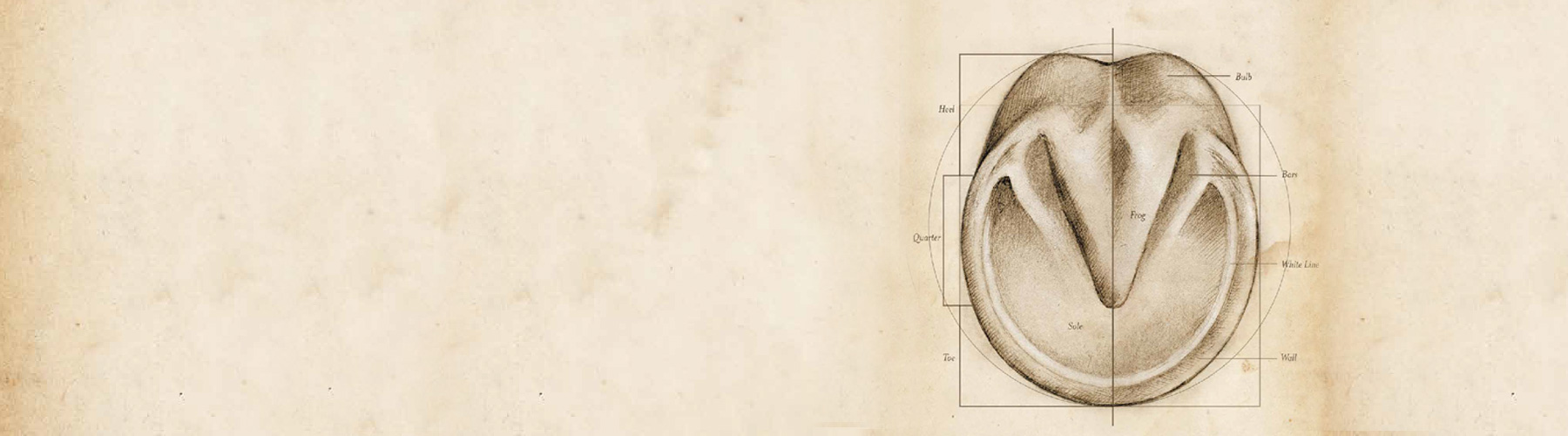

Anatomical Masterpiece

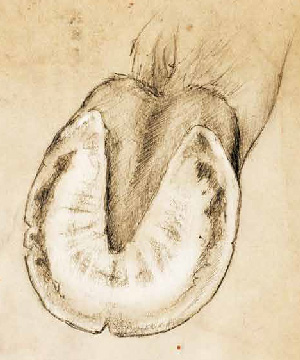

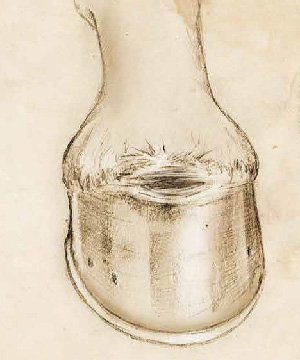

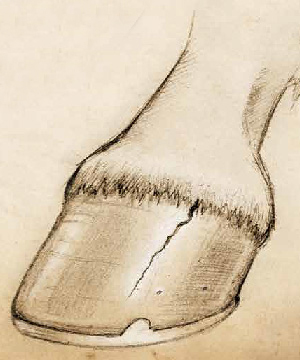

The basic anatomy of the horse hoof is familiar to most people. At the very top of the hoof is the coronary band, which is the primary source of growth and nutrition for the hoof wall. The hoof wall is the hard, outer layer of the hoof capsule that runs from the coronary band down to the ground and gives the entire foot its rigidity and weight-bearing strength. The hoof wall itself is actually made up of three layers that include the outer periople, a middle layer and an inner layer. When viewed from the bottom, the hoof can be divided into three main sections: the heel, quarter and toe. The hoof wall can also be viewed from the bottom of the hoof as the outer most layer that runs into the white line separating the hoof wall and the sole. The sole, which makes up the majority of the undersurface of the hoof, is softer than the wall due to more natural moisture and protects the sensitive structures within the hoof. The main role of the bars is to bear weight; they are the part of the wall that have turned inward from the heel to surround the frog. The v-shaped portion of the hoof that separates the heels is the frog, and it serves multiple functions. Because of its higher moisture content, the frog is more elastic and is a natural shock absorber. It aids in traction and heel expansion as well as circulation by pumping blood back to the heart.

What may be less familiar is the unseen hoof. The living, breathing, sensitive tissues underneath these familiar parts are charged with much of the growth, circulation and nourishment of the entire hoof. Analogous to the quick of the human fingernail, the corium is the part of the hoof that produces new hoof growth, or the hoof horn and contains an intricate network of blood vessels and nerves. The laminar corium (sensitive laminae) is laminae engorged with blood vessels. It attaches to the innermost layer of the hoof wall, in a Velcro-like way on one side and firmly attaches to the pedal bone on the other side. The solar corium (sensitive sole) contains hair-like laminae also teeming with blood vessels. It attaches to the sole and the frog and supplies nutrients for growth. The digital cushion resides on top of the frog and behind the pedal bone, viewed on the outside of the hoof as the bulbs of the heel. It is a tough yet elastic structure that reduces concussion to the foot and supports heel expansion as well as assisting in circulation. Lateral cartilages, the pedal bone and the navicular bone also make up the inner structure of the amazingly tough yet also delicate hoof.

The dread that accompanies words such as “foot abscess,” “quarter crack” and the insidious “laminitis” reinforces the incredible importance of the health of the hoof, as well as the fact that a compromise of it debilitates the entire horse. The health of the hoof is essentially an extension of the health of the horse, and nutrition provides a critical component in its well-being. Mark Silverman, DVM, MS of Sporthorse Veterinary Services, notes the harmonious marriage of nutrition and hoof health. “Good nutrition and a properly-functioning gastrointestinal system are critical to good hoof health. Having access to good quality nutrition is as important as regular hoof care,” says Dr. Silverman. There is a difference between providing adequate nutrition and good or therapeutic nutrition. Energy intake, protein and amino acids, fats and fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, along with clean water, are the specific nutritional areas that provide the integral foundation for hoof health, as well as the means for optimizing hoof health.

Hoof Spotlight

Common Problems & Nutritional Support

Hoof problems range from superficial to debilitating. Consulting your veterinarian and farrier is the best approach for hoof care and critical if the horse is experiencing duress. There are different methods to offer support for hoof issues that include corrective shoeing, topical treatments, wrapping, etc. Providing specific nutrients through the diet can be used as a preventative measure and therapeutically to decrease inflammation, support normal circulation and ensure the hoof tissue has the necessary building blocks to heal and rebuild.

Navicular Syndrome

Navicular syndrome, often called navicular “disease,” is a group of related abnormalities affecting the navicular bone and associated structures in the foot. Usually seen in both front feet, it most commonly describes an inflammation and progressive degeneration of the navicular bone and its surrounding tissues. It can lead to significant and even disabling lameness. It is more prevalent in competition horses with a tendency to affect Quarter Horses, Thoroughbreds and Warmblood breeds between the ages of 7 and 14. Conformation may also be a predetermining factor. The exact cause is not known, but damage to the navicular bone may occur due to a lack of blood supply or trauma to the bone. Damage may also occur to the deep flexor tendon, navicular bursa or navicular ligaments, which may all result in inflammation, pain and lameness. If navicular disease is suspected, contact a veterinarian who will likely perform flexion tests and nerve blocks and may use x-ray or MRI for diagnosis. The veterinarian and farrier may also use corrective shoeing to improve blood flow and lift and support the heel for comfort.

Supportive Products: Platinum Performance® DJ or Platinum Performance® CJ, Platinum Hoof Support, Osteon®, Platinum Longevity®

Laminitis

Laminitis is the most serious disease of the equine foot and causes pathological changes in anatomy that may lead to long-lasting, crippling changes in function. Laminitis is inflammation of the sensitive structures in the hoof called the lamellae, which holds the coffin bone tight within the hoof horn. This inflammatory condition is extremely painful and can lead to rotation of the coffin bone known as founder. There are multiple causes of laminitis. Nutritionally, it can be related to a high intake of sugar and starch, primarily from a high intake of grain mixes with cereal grains and molasses. Additionally, overconsumption of rich, lush pasture grass, particularly when a horse is unaccustomed to it can cause laminitic changes. Diets should provide enough energy to promote growth of the hoof wall and maintenance of an ideal body condition score between 4 to 6 out of 9. Excessive weight should be avoided to help prevent complications from obesity and insulin resistance, which can be associated with laminitis. Equine rations that provide a high concentration of non-structural carbohydrates from sugar, starch or fructans should be avoided because these dietary carbohydrates can also lead to complications from laminitis. If laminitis is suspected, contact your veterinarian and farrier for a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Supportive Products: Platinum Performance® GI, Platinum Hoof Support, Hemo-Flo®, Platinum Longevity®

White Line Disease

White line disease, also called seedy toe, is a widespread problem affecting the equine foot. Multiple causes have been proposed including excessive moisture, which softens the foot, as well as excessively dry hooves, which may form cracks or separations. Both of these scenarios allow an avenue for pathogens to invade. Another logical cause of the disease is mechanical stress due to an excessively long toe, poor general hoof conformation and several hoof capsule distortions. It is most commonly found by the farrier during routine hoof care and is characterized by a progressive separation of the inner zone of the hoof wall, beginning at the sole. The white line is the junction of the hoof wall and the sole. The separation occurs in the non-pigmented horn at the junction between the two main layers of the hoof horn. The disease process occurs secondary to a hoof-wall separation. Opportunistic and infectious bacteria and fungi may invade the separation and cause or compound disease. Field studies suggest that a higher dietary level of iodine, an anti-fungal, may offer support to resolve white line disease over a period of weeks.

Supportive Products: Platinum Performance® Equine, Platinum Hoof Support

Hoof Abscess

Caused by bacteria getting trapped inside the hoof, abscesses are a very common cause of acute lameness in horses. Trauma to the hoof sole caused by a puncture (nails, glass, etc.) may lead to bacteria and debris having access to the inner hoof and resulting in an abscess. Excess moisture may cause the hoof wall to soften and allow bacteria access through gaps in the white line. Conversely, extremely dry hooves may lead to brittleness and cracking of the hoof wall also lending access to bacteria. The hoof itself does not allow room for swelling, so as excess pressure builds up from foreign bacteria, it causes an extreme amount of pain resulting in severe lameness, often times seeming to occur overnight. In most circumstances, a veterinarian will be able to drain the abscess, with pain relief being nearly immediate and allowing rehabilitation to begin.

Supportive Products: Platinum Performance® Equine, Platinum Hoof Support

Hoof Cracks

There is a wide spectrum of hoof cracks and the severity of the crack depends on location, depth and site of origin. Grass cracks and sand cracks tend to be superficial flaws caused by the environment. Heel cracks, bar cracks and toe cracks are capable of causing extreme pain. Quarter cracks, in particular, are painful, difficult to manage and have a variety of causes. Quarter cracks involve the coronary band and grow downward. They are more likely than other types of cracks to bleed and become infected, leading to extreme pain and lameness. For all cracks, the farrier should be involved in assessment and will determine the best plan for repair and stabilization.

Supportive Products: Platinum Performance® Equine, Platinum Hoof Support

Think Positive: Energy Balance

Total energy or caloric intake directly correlates to growth rate of hooves. Ensuring that a horse is in a positive energy balance means that his total intake exceeds his output; the horse is maintaining or gaining weight. The diet should provide enough energy to promote growth of the hoof wall while maintaining an ideal body condition score between 4 to 6 out of 9. Overall energy balance is higher than maintenance requirements in several classes of horses, including those that are growing, lactating, breeding, working or exercising. If a horse has very poor quality hooves, consider total energy intake first. A horse in a negative energy balance will utilize protein to compensate for energy needs for maintenance or growth, etc. This may create a secondary protein or amino acid deficiency that will directly impact hoof quality. Research has shown that hoof wall growth was 50 percent greater in growing ponies that were in positive energy balance when compared with ponies on restricted diets with a reduced body growth rate. It is a common observation that when horses gain weight on lush, spring grass, they also grow hoof faster, highlighting that the perfect food for horses truly is fresh, green grass. The recommendations for total digestible energy for a 1,100-pound horse at maintenance is between 15.3 and 18.2 megacalories (Mcals), dependent on the individual horse’s metabolism. A rough estimate of forage by weight needed per day is about 2 percent of the total body weight or 22 pounds for a 1,100-pound horse; 22 lbs of “good” grass hay contains approximately 17.6 Mcals. This is an oversimplified example but a good demonstration that energy requirements for horses at maintenance can easily be met with forage alone.

The Importance of Protein

Protein is the core of a solid hoof. From the Greek word proteos, meaning “of primary importance,” protein makes up over 90 percent of the hoof wall on a dry matter basis. Protein deficient diets lead to general poor hoof quality as shown by reduced hoof growth and splitting or cracking of the hoof. Hoof tissue contains many amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein, and these amino acids are what actually affect the metabolism of the hoof and must be available in appropriate amounts in the diet. Digestible and high-quality protein supplies the horse with the amino acids essential for hoof growth. The availability and balance of the amino acids are more important than the general crude protein intake. For example, the amino acids, lysine and methionine, may be deficient even if the total crude protein in the diet is adequate. Both lysine and methionine are essential for hoof growth as they are necessary for producing all body proteins, including keratin. Keratin is an extremely strong specialized type of skin cell and is the major structural protein for the hooves, as well as skin, teeth, mane and tail. Keratin is responsible for the outer protective layer of the hoof wall as well as structural support. Keratin, keratin-associated proteins and the intercellular cementing substance are all made from amino acids, which are used to synthesize these structural proteins in the hoof wall.

The sulfur-containing amino acids, cystine, cysteine and methionine, play a key role in the development of the “cellular envelope,” also known as the marginal band, which protects horn cells against protein-degrading enzymes. Cystine and cysteine can actually both be manufactured internally from methionine. The pathway that converts methionine to cysteine is thought to be imperative in the production of a quality hoof. Methionine is a diet-dependent amino acid since it cannot be manufactured from other amino acids as is the case for several others. Methionine is necessary for integrity of the white line and along with lysine, is essential for hoof growth; both are necessary for producing all body proteins. As a primary constituent of keratin, methionine stimulates strong, healthy hoof growth and is essential to prevent cracked, brittle hooves.

PHOTOS BY DREW STOECKLEIN

Fats for Feet

Fats play a pivotal role in a healthy hoof as they retain the natural moisture and pliability of the hoof wall, resist the absorption of water from the environment and prevent bacteria and fungi from entering the hoof horn. Hoof tissue has 3 to 6 percent total fat, which works to bind cells together and aids in repelling water. Fatty acids are important nutrients for healthy hooves as they help in connecting hoof horn cells and sustain a permeability barrier. In grass, the ratio of omega-3 fatty acids to omega-6 fatty acids is between 4:1 to 6:1, which is ideal for the horse. However, the fragile omega-3 fatty acid content drops quickly and dramatically when grass is cut and cured to make hay. Omega-3 fatty acids will undoubtedly need to be supplemented back into the diet if the horse is on a hay-only diet. If grains are provided in the diet, omega-3 fatty acids will need to be added to balance the pro-inflammatory omega-6 fatty acid content from the grains, especially if the horse does not have access to pasture. Deficiency of fat can be seen in skin and hoof problems, which is a reason many horses with dry, splitting feet that do not respond well to other vitamin/mineral-specific supplements improve when supplemented with a formula that provides a good source of omega-3 fatty acids.

Take Your Vitamins

Several antioxidants are influential to equine hoof health, including beta carotene (precursor for vitamin A), vitamin C and vitamin E as they offer protection from oxidation at the membrane level. Vitamin A specifically is also necessary for keratin production. Vitamin C is influential in the production of collagen, which is incorporated into all connective tissues. Fresh grass provides adequate levels of all of these vitamins. However, the overall content drops when fresh grass is cut for hay. Unlike Vitamin C, which can be synthesized in the intestines of the horse to prevent maintenance deficiencies, beta carotene and vitamin E may require supplementation for horses without access to fresh grass to support hoof health.

The B vitamins play essential roles in every organ, tissue and cell, and all of them are needed for normal protein production and cellular metabolism. Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is synthesized from cobalt in the diet and is involved in blood cell formation to nourish hoof tissue. Biotin, a sulfur-containing B vitamin, is an important cofactor for several major enzymes and has a positive effect on the synthesis of intercellular glue used for cell-to-cell adhesion to strengthen the outer hoof wall layer. Supplementation with biotin leads to improved hoof wall strength and an increase in the rate of hoof growth. Biotin supplementation is particularly recommended for horses fed a high grain diet and not on pasture. The B vitamins are produced by the gut microbes, which protect the horse from a full-blown deficiency state. However, supplementation may be needed to reach a level of optimal health and to support hoof production.

Composition of the Hoof

Key Elements & Their Roles in the Equine Hoof

Proteins

- Keratin is responsible for the outer protective layer of the hoof wall as well as structural support.

- The sulfur-containing amino acids, cystine, cysteine and methionine, play a key role in the development of the “cellular envelope,” also known as the marginal band, which protects horn cells against protein-degrading enzymes.

Fats

- Fatty acids are important nutrients for healthy hooves as they help in connecting hoof horn cells and sustain a permeability barrier.

Vitamins

- Beta carotene (precursor for vitamin A), vitamin C and vitamin E offer protection from oxidation at the membrane level.

- Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is synthesized from cobalt in the diet and is involved in blood cell formation to nourish hoof tissue.

- Biotin, a sulfur-containing B vitamin, is an important cofactor for several major enzymes and has a positive effect on the synthesis of intercellular glue used for cell-to-cell adhesion to strengthen the outer hoof wall layer.

Minerals

- Manganese is an antioxidant trace mineral that protects the hoof cell membrane from oxidation.

- Calcium, a macromineral, is integral for hoof growth and strength.

- Zinc is present in high concentrations in normal hoof tissue and is critical for a variety of functions, including the normal cell division involved in the growth and repair of the hoof wall.

- Copper enables important enzymatic functions required for metabolism in rapidly dividing cells, such as hoof cells.

Mighty Minerals

Minerals are needed for virtually every process in the entire body of the horse, and growing and protecting hoof tissue is no exception. Providing the requirements needed for maintenance at whatever stage of life, the horse is in is extremely important. However, it is also important that minerals are in the correct proportion to each other since they interact with each other and can interfere with the absorption of another if levels are too high or too low. Dr. Silverman notes, “While biotin is probably the most common supplement people consider when trying to support good quality hooves, there are other nutrients, including lysine, methionine, copper and zinc, amongst others, that appear to be important to maintain good quality hooves.”

Manganese is an antioxidant trace mineral that protects the hoof cell membrane from oxidation. The macromineral calcium is integral for hoof growth and strength. Calcium is known to be essential as it is involved in the creation of sulfur cross-links between the hoof proteins and in the cohesion of cells to each other and initiates cell envelope formation. If calcium levels are low in the overall diet, supplying extra calcium to meet requirements may positively impact hoof quality as well as bone quality. Many horses show a noticeable improvement in hoof horn quality when diets are balanced for calcium.

Hoof quality suffers dramatically with inadequate levels of the trace minerals zinc or copper. Zinc and copper are two of the most common trace mineral dietary deficiencies around the world. A lack of either of these minerals can result in slow hoof growth and thin, weak walls. High iron intake, extremely common in horses, can compound the problem as it interferes with absorption of both these minerals. Significant improvement is typical for horses that receive adequate supplementation of zinc and copper. Zinc and copper are much needed for the hoof itself but also necessary for forming healthy tissue that attaches the outer hoof wall to the living tissue underneath. As antioxidants, zinc and copper also prevent fats and oils from oxidizing. Oxidative damage to the fats in the hoof structure break the protective seal on the hoof. This causes drying and weakening of the cementing “glue” between the cells.

Zinc is present in high concentrations in normal hoof tissue and is critical for a variety of functions, including the normal cell division involved in the growth and repair of the hoof wall. It is vital for the assembly of collagen and intercellular cementing substance. Zinc is also essential for a variety of enzymes that every metabolically-active cell needs. Zinc-dependent enzymes are involved in keratinization, which hardens and strengthens the hoof. Therefore, a deficiency in zinc will result in incomplete keratinization, which will result in a defect of the hoof horn.

Copper is versatile, and so it is incorporated into many areas of the horse’s body from skin and coat pigmentation, to brain development and function, to the synthesis and maintenance of connective tissues and in immune support. In the hoof, copper enables important enzymatic functions required for metabolism in rapidly dividing cells, such as hoof cells. Copper is involved in disulfide bond formation in keratin and cell envelope proteins, which connect hoof cells and influences overall rigidity of the hoof. When there is a copper deficiency, the bridges that hold keratin strands together are often compromised. This is the reason why low dietary levels of copper are often associated with weak or damaged hooves.

The Equine Hoof: By the Numbers

50%

Research has shown that hoof wall growth was 50 percent greater in growing ponies that were in positive energy balance when compared with ponies on restricted diets with a reduced body growth rate.

15.3-18.2

The recommendations for total digestible energy for a 1,100-pound horse at maintenance is between 15.3 and 18.2 megacalories (Mcals), dependent on the individual horse’s metabolism.

2%

A rough estimate of forage by weight needed per day is about 2 percent of the total body weight or 22 pounds for a 1,100-pound horse; 22 lbs of “good” grass hay contains approximately 17.6 Mcals.

90%

Protein is the core of a solid hoof. From the Greek word proteos, meaning “of primary importance,” protein makes up over 90 percent of the hoof wall on a dry matter basis.

3-6%

Hoof tissue has 3 to 6 percent total fat, which works to bind cells together and aids in repelling water.

9-12

Studies have shown that the equine hoof wall takes approximately 9 to 12 months to grow from the coronary band to the weight-bearing surface. Dietary changes, including supplementation, will only influence new growth.

The Art of the Hoof

The foundation of soundness in the horse is a healthy hoof. With its tough, impermeable outer wall, it is easy to overlook the fact that one layer below that hard exterior are living, breathing, circulating and very metabolically active inner tissues constantly growing and repairing. Regarding the hoof, but also applicable to the entirety of the horse, is the fact that outward health starts from within. What is different from the rest of the horse is that positive, quantifiable changes to the hoof take an extended period of time for results to be observed. Studies have shown that the equine hoof wall takes approximately 9 to 12 months to grow from the coronary band to the weight-bearing surface. Dietary changes, including supplementation, will only influence new growth. While we are a society that is programmed for instant gratification, redemption of the hoof requires patience and perseverance for a slow but worthwhile transformation. Key dietary components for equine hoof health that include energy, protein and amino acids, fats and fatty acids, vitamins, macrominerals and trace minerals, play a prominent role in maintaining hoof integrity. Good health fuels good hooves. But it seems also that good fuel behooves good health.

by Emily Smith, MS,

Platinum Performance®