Renowned Equine Surgeons and Colic Experts Drs. Diana Hassel and Liara Gonzalez Describe How Novel Research, Evolving Diagnostics and Treatments and a Firmer Grasp on Prevention are Providing Horses Improved Odds of Survival and Recovery

“Anesthesiologists have drastically improved the status of critically ill (equine) patients undergoing surgery, our critical care work has evolved, and we have an increased understanding of fluid therapy and other support mechanisms to help improve the outcomes of these horses,” says Dr. Diana Hassel. “These factors, when combined, have contributed to improved prognoses.”

“Anesthesiologists have drastically improved the status of critically ill (equine) patients undergoing surgery, our critical care work has evolved, and we have an increased understanding of fluid therapy and other support mechanisms to help improve the outcomes of these horses,” says Dr. Diana Hassel. “These factors, when combined, have contributed to improved prognoses.”

Of any condition affecting horses, colic tends to lead the pack in terms of its fear factor. As humans, we naturally fear the unknown, and with no definitive, singular cause, colic remains a challenge for both veterinarians and their horse owner clients. By definition, colic is broadly associated with any significant discomfort related to the abdomen. Ask any equine veterinarian, however, and they’ll tell you that the condition is wildly nuanced, still relatively enigmatic and deeply complex. “Colic is a very general term,” explains Liara Gonzalez, DVM, PhD, DACVS, an equine veterinarian and board-certified surgeon at North Carolina State University’s celebrated College of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Gonzalez is a worldwide authority in equine intestinal disease, with her research helping to transform hard science into clinically relevant therapeutic interventions for horses. “We don’t definitively understand what causes colic,” she continues. “While we have some ideas, the most well-cared-for horse still has the potential to colic. There are numerous causes, with some being preventable and others being out of our control. Unfortunately, despite a horse owner’s best efforts, it can still happen.”

Though numerous questions still surround the topic, equine veterinary medicine has undeniably advanced its understanding and capabilities related to the condition, with tremendous improvements seen in diagnostics, anesthesia, surgical techniques and recovery protocols. It wasn’t long ago that a team of veterinarians at the University of California, Davis, one of the nation’s top-ranked veterinary schools, hovered over an equine patient to perform the first successful colic surgery in 1968. Today, horses survive surgical colic at an average rate above 90%, but with that success comes unanswered questions that veterinarians are determined to answer. “We still haven’t mastered prevention,” says Diana Hassel, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVECC, of the famed Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in Fort Collins. Dr. Hassel has been a pivotal figure for over two decades in the study of equine colic and as a surgeon helping to further clinically relevant information related to the disease. “So much progress has been made,” she points out. “Anesthesiologists have drastically improved the status of critically ill (equine) patients undergoing surgery, our critical care work has evolved, and we have an increased understanding of fluid therapy and other support mechanisms to help improve the outcomes of these horses. These factors, when combined, have contributed to improved prognoses.”

Perhaps what’s most difficult to accept with colic is how indiscriminate it is. The finest breeding, care and housing don’t protect a horse from all risk. Colic can impact virtually any horse, and regardless of best efforts, some cases still pose immense challenges to treat and recover.

What Causes Colic?

While several risk factors for colic have been identified, there is no singular cause that can prevent colic from materializing. What is known is that the most prolific cause may in fact be the least complex: gas. “It’s referred to as spasmodic colic,” Dr. Gonzalez explains. “These horses can be induced from stress. That’s one of the key reasons we should always be asking ourselves as veterinarians and owners, ‘How can we reduce stress in our horses’ lives?’ That would likely reduce the amount of colic we see. To do that, we’re paying attention to feeding more of what nature intended horses to eat, giving these natural grazers access to quality forage all day long; paying close attention to appropriate intake of grains, concentrates and supplements; and reassessing how we manage them while trailering, showing and competing.” Each factor can contribute to gut dysbiosis, an imbalance in the gut microbiome, and resulting gas if not properly managed, highlighting the role that diet and lifestyle management play. “There are numerous risk factors that vary dependent on the type of colic,” adds Dr. Hassel. “In general, these can range from dietary indiscretions, changes in diet, ingestion of different types of feed or moldy feed, stress factors, cribbing and geographical location. So many things can cause dysbiosis somewhere in the gut that can result in colic.”

Aside from outside influences, the anatomy of the equine digestive tract itself is a key culprit in why horses are prone to the condition. “The horse’s abdominal tract is not well-attached to its body wall,” explains Dr. Gonzalez. “There’s a great study out of Colorado State University that shows how much the colon can naturally move within the horse’s abdomen at any given moment. We know that that movement may be OK if there isn’t excessive gas, which can cause the colon to get stuck in positions it’s not meant to be in, leading to colic. This also shows how much we still don’t know about the equine abdomen.”

©2025 PLATINUM PERFORMANCE/TOPLINE DESIGN

©2025 PLATINUM PERFORMANCE/TOPLINE DESIGN

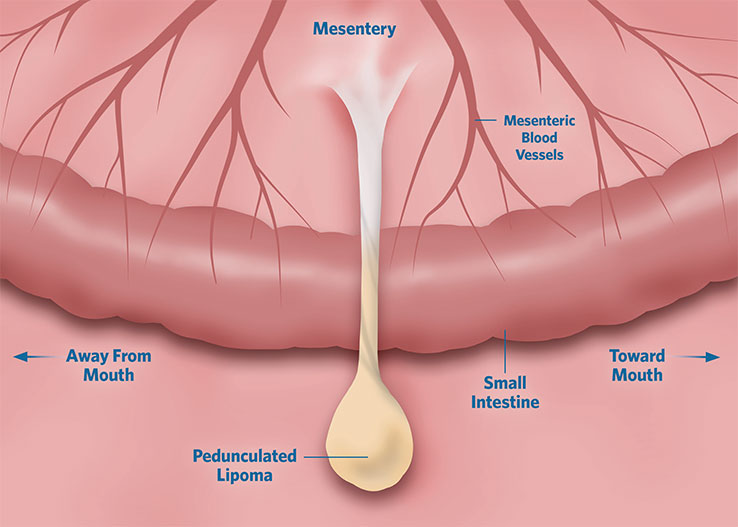

Segment of small intestine showing a lipoma, which has developed from the mesentery (thin connective tissue sheet which houses vessels and nerves). The weight of the lipoma causes stretching of the support tissue, forming a long stalk, known as a “peduncle.”

©2025 PLATINUM PERFORMANCE/TOPLINE DESIGN

©2025 PLATINUM PERFORMANCE/TOPLINE DESIGN

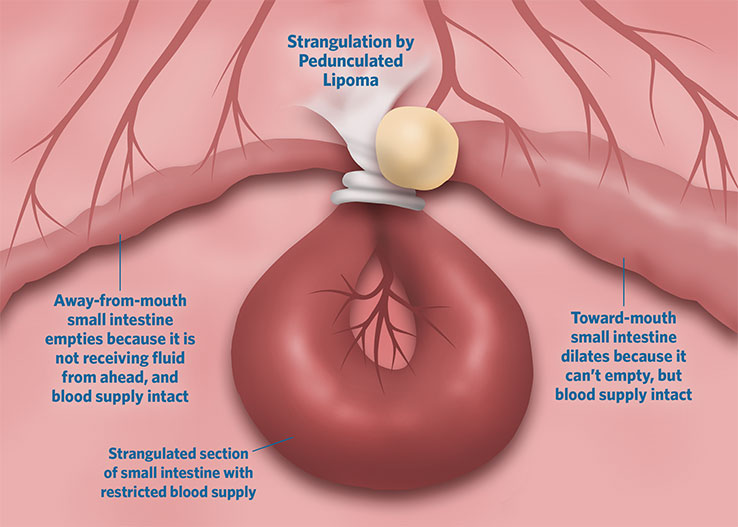

Pedunculated lipoma wrapped tightly around a segment of small intestine, constricting its blood supply.

The Small Intestine

Colic cases are broadly classified into those affecting the small intestine and cases involving the large intestine, which is also referred to as the large colon. Colic in the small intestine is common and more prone to negative outcomes because of its tendency to skew more severe. “When we’re talking about the small intestine, we’re talking about some of the worst colic cases,” affirms Dr. Gonzalez. “The intestine and the small intestine specifically are very sensitive to loss of oxygen. The intestine is not a privileged organ. In other words, when we’re taxing our bodies and undergoing exercise, blood gets shunted to other parts of the body that are privileged, like our heart, brain and larger muscles. Blood travels away from the intestinal tract, which can contribute to abdominal cramping. When we talk about the small intestine and strangulations or ileal impactions, for instance, there is a reduction of blood supply to a segment of the intestine, which is referred to as ischemia.” When ischemia occurs, there is a progressive loss of the vital lining of the intestine that provides a critically important barrier function. “We all have noxious bacteria and toxins within our intestinal tract,” she adds, “but it’s that lining that prevents those materials from escaping the lumen (the passageway where food moves through the digestive tract) and passing through the damaged intestinal lining, then having free access to our systemic circulation. Once that barrier is broken down, the horse can then develop complications from colic to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), laminitis and more.” In colic cases ranging from strangulating lipomas (benign fatty tumors) to epiploic foramen entrapments (a life-threatening condition where a portion of the small intestine becomes trapped in a small opening between the liver and pancreas) or even ileal impactions (a blockage in the ileum — the final section of the small intestine), segments of the small intestine can become so compromised that the surgeon loses confidence that it can heal and regain normal function. In these cases, that section of small intestine will be resected, then the two healthy ends of the intestine will be reattached in a procedure known as an anastomosis. “Unfortunately, a lot of these issues tend to occur at the end of the small intestine directly before it enters the cecum (a large muscular sac located at the junction of the small and large intestines). Everything ahead of that point has been distended and becomes enlarged by the time the horse is in surgery. The intestine essentially becomes stretched for an extended period; it’s then unable to return to its normal size and can’t contract appropriately to pass food from the front to the end where it enters the cecum, known as ileus. Those horses tend to reflux and pose significantly greater challenges,” Dr. Gonzalez describes of surgical complications in colic cases involving the small intestine.

Interestingly, “criticalists,” or board-certified veterinarians specializing in emergency and critical care for horses, have added expertise to difficult cases involving the small intestine, helping improve outcomes together with their surgical colleagues. “It’s often the criticalists that are stabilizing these horses before we take them to surgery,” explains Dr. Gonzalez. Where patients may have previously been rushed into surgery in all cases, many larger institutions now have criticalists who help stabilize the patients preoperatively. “That stabilization is an important component,” agrees Dr. Hassel, who, aside from her standing as a top-tier surgeon, is also a criticalist. “To some extent, depending on the lesion, the most crucial element is time, so we’ll move quickly in those cases. However, when the case allows for it, criticalists can help get the horse stable enough to better withstand the anesthesia, surgery and recovery.”

Strangulating obstructions can be significantly more serious and can include volvulus obstructions where a section of the large intestine twists or tangles around itself causing a blockage that can cut off vital blood supply.

Strangulating obstructions can be significantly more serious and can include volvulus obstructions where a section of the large intestine twists or tangles around itself causing a blockage that can cut off vital blood supply.

“To some extent, depending on the lesion, the most crucial element is time, so we’ll move quickly in those cases. However, when the case allows for it, criticalists can help get the horse stable enough to better withstand the anesthesia, surgery and recovery.”

— Diana Hassel, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVECC, Colorado State University

Additional forms of non-strangulating obstructions can be seen in enteroliths (mineral stones of varying sizes, formed around a nidus and comprised of magnesium, ammonium and phosphorus), sand impactions and displacement cases where the blood supply to the large intestine remains intact but a portion of the large intestine moves out of its normal position, causing an obstruction.

Additional forms of non-strangulating obstructions can be seen in enteroliths (mineral stones of varying sizes, formed around a nidus and comprised of magnesium, ammonium and phosphorus), sand impactions and displacement cases where the blood supply to the large intestine remains intact but a portion of the large intestine moves out of its normal position, causing an obstruction.

The Large Intestine

Similar to the small intestine, colic cases involving the large intestine can be broadly classified as either strangulating obstructions (twisted or entrapped intestine) or non-strangulating obstructions (feed impaction or displacement) and can also include an inflammatory component (colitis) or infarctive disease (blockage of blood supply). Of non-strangulating cases in the large colon, Dr. Hassel explains, “These obstructions are probably one of the more common types of colic we see in the field. These are the cases when your horse stops passing manure, your veterinarian comes out, they administer a laxative, provide fluids and a little bit of pain control, and often the horse will start passing manure again after a period of time.” Additional forms of non-strangulating obstructions can be seen in enteroliths (mineral stones of varying sizes, formed around a nidus and comprised of magnesium, ammonium and phosphorus), sand impactions and displacement cases where the blood supply to the large intestine remains intact but a portion of the large intestine moves out of its normal position, causing an obstruction.

In contrast, strangulating obstructions can be significantly more serious and can include volvulus obstructions where a section of the large intestine twists or tangles around itself causing a blockage that can cut off vital blood supply. “Many of these cases tend to twist at a location that is very difficult to access,” says Dr. Hassel of the challenge surgeons encounter. “These can therefore encompass the entire large colon, all the way down to where the cecum and the small intestine tie in the base of the large colon. It can sometimes be impossible to correct these cases safely without spilling intestinal contents.” Additionally, intussusception cases involve a portion of the large intestine infolding onto an adjacent section of intestine (like a drooping tube sock), setting the stage for a blockage and potentially compromising blood supply as well. “There’s also the small colon, which is still part of the large intestine, and can experience its own conditions as well,” points out Dr. Hassel. “We see occasional strangulating lipomas in this area,” she explains, referencing benign fatty tumors that can wrap around the intestine, cutting off blood supply and causing a potentially life-threatening colic. “Additionally, infarctive lesions involve a focal region where the bowel has lost its blood supply (causing tissue to die). It could be venous or arterial or a combination of both. In these cases, we may see a focal area with marked thickening, and if it’s a more advanced case, it may actually be thin walled, indicating it’s about to rupture into the abdomen,” explains Dr. Hassel. “These are very difficult to manage. We’re talking about a large surface area and the presence of bacteria and other components within the lumen of the large intestine that are not meant to be exposed to the horse’s systemic circulation. If that exposure happens, it can result in severe life-threatening complications.” Indeed, strangulating obstructions of the large intestine can be both time sensitive and extremely difficult for a surgical team to operate successfully due to a myriad of complications ranging from inaccessibility to tissue necrosis and the threat of systemic exposure to harmful toxins within the large intestine. “You don’t have a lot of time,” agrees Dr. Gonzalez. “If they twist and twist tightly, intestine dies very rapidly. We typically have less than a three-hour window from onset to when that tissue is no longer viable. That’s incredibly short when you consider the time it takes a veterinarian to see the horse in the field, deduce what’s happening, load the horse on the trailer and get it to a referral hospital and into surgery. To accomplish that in under three hours is rarely possible.”

“As surgeons, we have the best interest of the horse in mind. We make quite an effort when a horse comes in to prove ourselves wrong; we ask ourselves, ‘Does this horse actually need colic surgery?’ We understand, even in the simplest colic surgeries, it’s still a major event, both financially and for the horse.”

— Liara Gonzalez, DVM, PhD, DACVS, North Carolina State University

Often the clinical signs noted in a field examination, coupled with pain level and poor or shortened response to analgesics, are conclusive enough diagnostically to know if a colic case requires transfer to a referral hospital for surgery or not.

Often the clinical signs noted in a field examination, coupled with pain level and poor or shortened response to analgesics, are conclusive enough diagnostically to know if a colic case requires transfer to a referral hospital for surgery or not.

The Importance of Time

Time is critical when a horse is facing a surgical lesion, very often making the difference between a successful outcome and one with greater complications or, in some cases, failure. “The earlier you can get them to a surgical facility, the better,” agrees Dr. Hassel. But how do you know if a colic case requires transfer to a referral hospital for surgery and when do you make that call? “The really critical factors are pain level and response to analgesics,” Dr. Hassel explains. “Also, what does the field veterinarian’s physical exam show, and what is the rectal exam telling them?” Often the clinical signs noted in a field examination, coupled with pain level and poor or shortened response to analgesics, are conclusive enough diagnostically. “As surgeons, we have the best interest of the horse in mind,” Dr. Gonzalez says. “We make quite an effort when a horse comes in to prove ourselves wrong; we ask ourselves, ‘Does this horse actually need colic surgery?’ We understand, even in the simplest colic surgeries, it’s still a major event, both financially and for the horse.” Perhaps one of the key communications equine surgeons would encourage is this: Don’t wait, refer earlier rather than later, and ensure that horse owners are informed as to the options in front of them and the process ahead. Sometimes even with advanced diagnostics being deployed in a hospital setting to help confirm a diagnosis, the final call to operate (or not to) comes down to a gut feeling based on the surgeon’s experience and ability to read the horse’s behavior. “I’ve absolutely taken horses to surgery purely based on pain,” says Dr. Gonzalez. “I had no concrete evidence. In fact, on paper it was the opposite. The rectal exam was negative, and diagnostics were relatively benign, but I could not control the animal’s pain. Sometimes, we don’t know for sure, but we have a feeling; we have a sense.”

If there’s a lesson to be gleaned from equine surgeons, it’s not to wait. Get to the referral hospital when time is on the horse’s side and more tools are available to best assess the case. “We can dig deeper, thoroughly evaluate blood work, consult pathologists, look at abdominocentesis (a sample of the fluid surrounding the intestines) and be ready to go quickly if the case requires surgery,” summarizes Dr. Gonzalez.

“We have so many great surgeons that are training other surgeons to approach these cases with an open-minded perspective, adapt to changes and evolve our techniques,” says Dr. Diana Hassel. “Because of this, we’re seeing better outcomes all the time.”

Advancements in Surgical Treatment

When a colic case requires surgery, horse owners can be buoyed by the remarkable improvements that have been achieved in recent years. “A lot of our progress in obtaining more successful outcomes as surgeons is due to superior methods in suturing, optimizing the luminal diameter and in avoiding blood supply issues,” reflects Dr. Hassel. “We have so many great surgeons that are training other surgeons to approach these cases with an open-minded perspective, adapt to changes and evolve our techniques. Because of this, we’re seeing better outcomes all the time.” Long-term, it’s inevitably the horse that benefits from this collegiality amongst surgeons, criticalists and the veterinary team at the helm of patients’ postoperative care. “We’re even more thoroughly considering the incision itself,” adds Dr. Gonzalez. “We’ve learned that when opening the abdomen, one single, sharp dissection is much better than if we lift our scalpel blade and do multiple cuts. We were creating numerous wounds that are then harder to heal and can allow more spaces for bacteria to grow.” There’s been significant research applied to establishing the most appropriate and effective way of closing the abdomen as well. In the past, the mindset was to place sutures as close as possible and use them liberally. “We now know there’s an ideal distance between sutures. So, even our approach to the incision, which seems so simple, has evolved for the better, as has our technique at nearly every stage of colic surgery,” Dr. Gonzalez says of the progress achieved. From the method and number of times that the intestine is handled during surgery to how the abdominal incision is closed at the end of the procedure, the number of knots used when suturing to the way an incision is covered and supported for optimal stability immediately postoperatively; it all matters, and it all plays a role in improving outcomes for surgical colic cases.

“One of the biggest things in my career thus far has been our appreciation for managing pain,” highlights Dr. Gonzalez. “Pain disrupts healing, so we’re much more aggressive about pain management, and we’re now using continuous rate infusions of different types of pain medications while paying close attention to not hindering motility.” With colic patients, maintaining gut motility, the muscular contractions that move food through the equine’s digestive tract, especially postoperatively, is imperative. To do so, veterinarians must delicately balance pain management with stimulation of eating and swallowing. “We’re often introducing food early in the postoperative process while perhaps supplementing the horse either intravenously or orally to help provide the energy necessary to recover faster. Over the span of my career, I’ve watched how we have been more active and aggressive about introducing things that ultimately help these horses recover,” observes Dr. Gonzalez. Pain management in particular has seen several important evolutions, even in the past few years alone. Some of the newest techniques involve ultrasound-guided celiac plexus blocks to increase intestinal motility, a procedure that involves injecting anesthetic near the celiac plexus, a complex system of nerves and ganglia near where the blood vessels supplying the intestines branch from the aorta. “While this technique is still being used primarily in a clinical research setting, it’s showing potential to improve motility and reduce pain,” explains Dr. Hassel. Additionally, intercostal nerve blocks (injecting local anesthetic near the intercostal nerves that run alongside the ribs) are being used to manage postoperative pain related to incisions in the abdominal and thoracic wall. “This sets them up for a better start in the postoperative period. If the horse is in horrible pain and throwing itself around the stall, lactate is high, and we’re setting ourselves up for failure from the beginning in terms of recovery,” cautions Dr. Hassel. “These pain management techniques have made a big difference.”

COURTESY PHOTO

Dr. Diana Hassel in colic surgery.

COURTESY PHOTO

Complications

Unfortunately, even with the very best in technology, technique and veterinary skill, outliers can cause complications during surgery and postoperatively. The opportunity for infection and secondary challenges to arise during surgery and in recovery is certainly present. “We’re watching closely,” assures Dr. Gonzalez of the constant attention being given to postoperative colic surgery cases by the recovery team. “We’re monitoring for signs of infection at the incision; we’re looking for various telltale signs that can differ if we’re dealing with the small intestine compared to the large intestine; there can be infections at the catheter site; we can see thrombosis of the vein; laminitis is always a risk; and of course, we’ve just handled a lot of toxic material in the intestine, which can have risk for the horse in terms of leakage of those toxins and that bacteria systemically. There’s a spectrum in terms of complications, from things we see frequently to challenges that are rarer but can happen.”

A particularly difficult complication that can present postoperatively is reflux. “Horses cannot vomit,” Dr. Gonzalez explains as a key factor in reflux. “Because of this, the intestine sometimes won’t effectively move fluid down into the colon. It can then become backed up and go into the stomach.” In severe cases, the stomach can expand so greatly due to fluid that gastric rupture can occur. To avoid that fatal occurrence, veterinarians pass a nasogastric tube through the nostril to the animal’s stomach, creating a conduit of sorts to relieve the pressure and remove the fluid buildup. This approach can be used in postoperative cases experiencing reflux and as a diagnostic tool in the field as a horse is displaying colic symptoms. “Diagnostically, we use this method to determine if a colic case is an enteritis, inflammatory or caused by an obstruction spurring fluid buildup,” says Dr. Gonzalez. “In hospitalized cases, however, we’re asking ourselves, ‘How distended was the intestine? How much did we have to manipulate that intestine intraoperatively? Each of these factors can impact the signaling that controls motility and thus set the stage for reflux.”

Dr. Laura Javsicas ultrasounds a horse.

Dr. Laura Javsicas ultrasounds a horse.

“The microbiome is just as critical for horses as it is for humans and any other mammal. The bugs (bacteria and other microbes) in our gut and our entire body are critical to the function of every body system — our nervous system, immune system, anything. You name it, and it’s affected by both beneficial and pathogenic bacteria, particularly in our gut.”

— Diana Hassel, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVECC, Colorado State University

The Microbiome

While gut motility is imperative, colic surgery recovery is closely tied to the gut microbiome and how that crucial environment is disrupted leading up to colic, with medical treatment during colic surgery and how it begins to stabilize postoperatively. “The microbiome is just as critical for horses as it is for humans and any other mammal,” explains Dr. Hassel. “The bugs (bacteria and other microbes) in our gut and our entire body are critical to the function of every body system — our nervous system, immune system, anything. You name it, and it’s affected by both beneficial and pathogenic bacteria, particularly in our gut. After colic surgery, we know there are considerable changes to the gut microbiota, especially when we are rinsing out impactions and flushing out much of the ingesta within the intestinal tract that is needed to repopulate a healthy gut microbiome.” Several factors are considered to support the gut microbiome in colic cases and post colic surgery. The fiber provided by hay, for instance, is crucial to kickstart motility in the hindgut, with beneficial bacteria working to ferment fiber and begin to repopulate a healthy gut environment. Yeast-based probiotics and prebiotics are also an important tool for veterinarians to support repopulation of the gut and provide complimentary support while patients are often on a course of postoperative antibiotics. “Since these horses are always on perioperative antibiotics, I’ll usually put them on a probiotic as well to support gut health and help reduce the risk of antibiotic induced colitis in their compromised gastrointestinal tract,” confirms Dr. Hassel. “I’ve done studies with both probiotics and prebiotics, assessing the impact on exposure to antimicrobials. These horses are getting antimicrobials for variable amounts of time, sometimes just a few doses and sometimes for three to seven days depending on the case. In my studies, I’ve shown probiotics to have a beneficial impact. They can dramatically change the metabolome, which are the small molecule metabolites produced by these bugs, to positively move it more toward normal.” Achieving a healthy repopulation of vital beneficial bacteria can be imperative to the healing process within the gut environment after colic surgery, setting the horse up for a more diverse gut microbiome and thus a more successful long-term recovery. “What we do nutritionally and the choices we make can help reverse some of the negative impacts of colic surgery on the gut microbiome,” affirms Dr. Hassel.

The Dietary Component

Probiotics and prebiotics have shown beneficial effects related to the gut microbiome in healthy horses as well as those dealing with colic and other ailments; however, there are numerous dietary factors to consider from a preventive standpoint related to colic specifically. “Diet is probably the No. 1 factor that contributes to these various gastrointestinal disturbances,” says Dr. Hassel emphatically. “It starts with gas production and inflammation that can result in changes to the diet that may not be executed as thoughtfully as they should be. Horses are big, but they’re delicate creatures. You can’t just change their food from one second to the next or put them suddenly out on a grass pasture when they haven’t been grazing. Any adjustments need to be made slowly.” Veterinarians and surgeons like Drs. Hassel and Gonzalez see numerous horses struggling with gas resulting from dietary changes, which can also be related to recurrent colics. “The number one complication of any colic is colicking again in the future,” points out Dr. Hassel. “Whether they have surgery or not, they’re at high risk for colicking again if they’ve been managed aggressively by a veterinarian for colic at any point.” One preventive approach she has taken in recent years is moving many of her post colic patients to what she refers to as a “low-residue” diet to reduce gas production. “We’re eliminating very fibrous, less energy dense, lower-quality feeds and instead sticking with quality forage and a finer-ground feed while providing other nutrients like the always-beneficial omega- 3 fatty acids, for example, as well as appropriate vitamins and minerals that these horses (and most horses) need. We’ve had some success with this, but we’re still gathering data,” she says of her continued work. “There is some early evidence that this may be helpful for some of these high gas producers that keep displacing their colons. Generally speaking, nutrition is a cornerstone when it comes to health, not just for us, but for our horses as well. Having a good balanced diet with some diversity in there can be beneficial, but you also want to keep it very gradual with any changes and adapt to what your individual horse needs, keeping in mind that continuous feeding factor. We rarely have issues with those horses that are out on pasture all the time.”

“Biomarkers are an exciting area. We have been working on specific biomarkers that can help to differentiate between inflammatory and strangulating types of colic.”

— Liara Gonzalez, DVM, PhD, DACVS, North Carolina State University

As colic remains a disease shrouded in a certain mystery and coupled with fear, there is reason to celebrate the significant strides made over the last several decades in taking a once catastrophic diagnosis to one that now often has a positive prognosis.

As colic remains a disease shrouded in a certain mystery and coupled with fear, there is reason to celebrate the significant strides made over the last several decades in taking a once catastrophic diagnosis to one that now often has a positive prognosis.

Pushing Onward

Important progress has been made in pain management, advanced diagnostics, fluid support, improved surgical techniques, better recovery protocols and heightened nutritional intervention. Past those discoveries, early diagnosis and outcome prediction have come into focus. “Biomarkers are an exciting area,” highlights Dr. Gonzalez. “We have been working on specific biomarkers that can help to differentiate between inflammatory and strangulating types of colic.” Many inflammatory colic cases are successfully treated medically rather than surgically, and biomarkers could allow for earlier diagnosis, allowing horses to potentially avoid surgery thanks to better information. Additionally, Dr. Gonzalez and her team have zeroed in on stem cells as a means of determining intestinal viability. Their goal is to allow surgeons someday soon to better (and more quickly) determine if affected sections of intestine will have a good chance at recovery, potentially avoiding resection where it may not be necessary. “ ‘Will this intestine heal? Will this horse recover?’ These are the questions we have as surgeons that we’d love to establish more concrete predictions for,” says Dr. Gonzalez. “These owners are investing a lot of time and a lot of money, and I would love to be able to tell them table side that their horse will survive.” Her team is examining affected intestine to determine if stem cells are still present and if they’re proliferating. “The intestine has an amazing capacity to regenerate, and if we don’t need to resect it then the length of surgery is much shorter and the risk for certain complications goes down. There are so many opportunities here,” she says excitedly. Beyond stem cells, her team is also pursuing enteroids (laboratory-grown models of equine intestine), organoids (3-D models derived from intestinal tissue) and a “mini gut” model (type of organoid used to study intestinal disease) as ways to test therapeutics. “These enteroids, organoids and mini gut models are basically the real inner lining of the intestine. They have all the cells that the inner lining has, including stem cells, and they grow. It’s a way that, without testing things directly on horses, we can instead test it in a dish, and we can say, ‘Yes, this is likely to help the intestine repair itself.’ ” Additionally, and perhaps the newest research focus as it relates to equine colic, a machine has been developed that can maintain a segment of intestine for a period, allowing researchers to test therapeutics that could be given within the blood supply or the lumen, applying them to that section of intestine. “We’re creating a controlled injury in a lab setting, then letting the intestine repair while we apply different therapeutics.” It’s all very next-level science, certainly, but the amount of innovation and technology being applied for real clinical progress is incredible. “The sky’s the limit. It’s an exciting road doing advanced research in colic, and my goal is that these things can be applied sooner rather than later to help treat horses more effectively but also to help our veterinary team obtain the best outcomes for our patients,” says Dr. Gonzalez with optimism.

As colic remains a disease shrouded in a certain mystery and coupled with fear, there is reason to celebrate the significant strides made over the last several decades in taking a once catastrophic diagnosis to one that now often has a positive prognosis. With more research-backed improvements on the way, the mystery clouding colic will continue to fade, but as in most disease states, prevention remains the most powerful and simplest of tools. “As a horse owner, know your own horse, be proactive, optimize their nutrition and take a preventive approach,” Dr. Hassel encourages. “It’s simple things,” adds Dr. Gonzalez. “Even choosing your hay source wisely and knowing that the practice of a horse continually chewing and processing hay is so important. Those things alone can be huge in terms of prevention.” From the great minds of the finest veterinary research institutions and on into the hands of practicing surgeons, veterinarians in the field and with horse owners in their everyday care, small steps can lead to optimal long-term health for our horses, giving us greater peace of mind and the gift of more time in the saddle.

Subscribe to the Platinum Podcast

Colic

Hear renowned equine surgeons and colic experts, Drs. Diana Hassel and Liara Gonzalez, discuss colic, including the latest in what we know, what questions remain and how horses — now more than ever before — have the best chance at not just surviving colic surgery but thriving after recovery.

Listen Now