Examining Common Factors Affecting a Dog’s Ability to Move Comfortably, and How Top Veterinarians Work to Prevent, Treat and Rehabilitate Those Conditions and Injuries

For so many, dogs are a part of everyday life. They’re fixtures within families, and when health struggles occur in the family pet, those problems take a very visible center stage. Like humans and horses, dogs can struggle with numerous mobility conditions and injuries affecting joints, cartilage, tendons and ligaments. These hindrances can stem from normal age-related ailments to inflammatory conditions, degradative enzyme damage, traumatic injury or even genetic predisposition (depending on the breed). Dr. Felix Duerr, who earned his veterinary degree at the School of Veterinary Medicine in Hanover, Germany, is a diplomate of both the American College of Veterinary Surgeons and the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, his ACVSMR specialty focuses on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of injuries and conditions related to physical activity in animals.

In 2021, he was awarded an endowed chair in Orthopedic Medicine and Mobility at the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at Colorado State University (CSU) in Fort Collins. On the faculty since 2011, he also leads orthopedic clinical trials and the Small Gait Laboratory at CSU’s James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital. His work there is as a clinician and researcher, treating four-legged patients while also studying the causes of canine lameness. Dr. Duerr’s efforts center on helping pioneer treatments and rehab protocols to help dogs maintain comfort, restore range of motion and heal from disease and injury. It’s a fascinating field of study that has evolved significantly in recent decades, now achieving dramatically improved diagnostic imaging and novel treatment techniques from targeted nutritional intervention and pharmaceutical support, to surgical solutions with complete joint replacements and numerous modalities in between.

PICTURE COURTESY OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY/DR. FELIX DUERR

“We see unique challenges with canine patients as quadrupeds (four-footed animals), but perhaps the biggest difference is that dogs complain a lot less than people or horses. Equine and human surgeons can be horrified when they see the amount of arthritis that our canine patients have while still actively walking around.”

— Dr. Felix Duerr, Colorado State University

Common Factors Affecting Canine Mobility

Any dog owner will tell you that these animals are unique for innumerable reasons. Orthopedically speaking, however, there are many similarities between the joints, cartilage, tendons and ligaments in a dog’s limbs to those holding the other end of the leash. There are differences as well: cartilage thickness; a dog’s propensity for traumatic injuries; and the frequency of disorders and injuries impacting hips and elbows — to name just a few. “We see unique challenges with canine patients as quadrupeds (four-footed animals),” Dr. Duerr points out, “but perhaps the biggest difference is that dogs complain a lot less than people or horses. Equine and human surgeons can be horrified when they see the amount of arthritis that our canine patients have while still actively walking around.” These resilient creatures handle a lot, but their owners can assist by recognizing subtle changes in their mobility and with the assistance of veterinarians intervene before the disease progresses significantly.

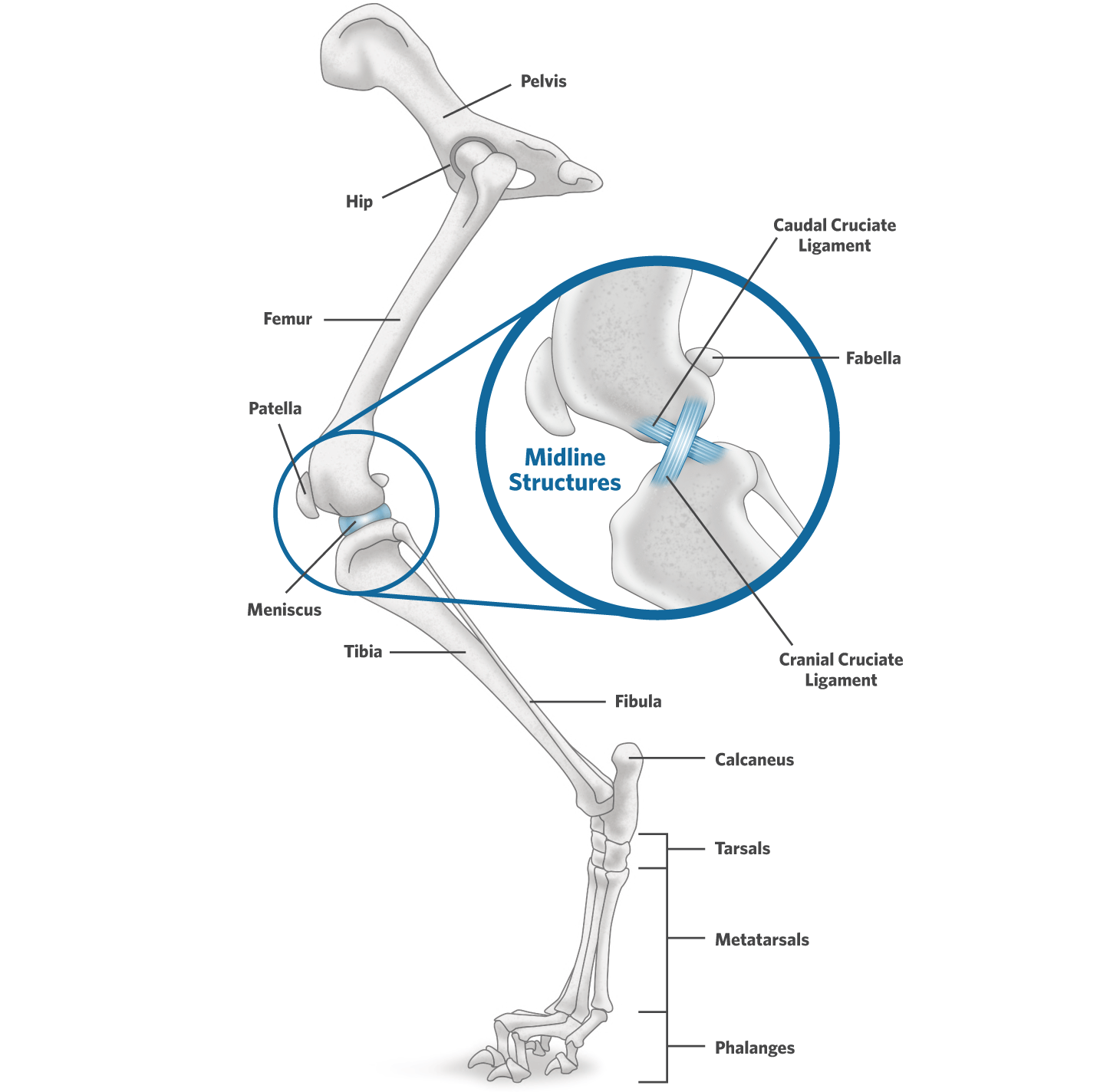

In addition to arthritis, veterinarians also commonly treat soft tissue injuries most often related to muscle or tendon tears, damage to the menisci (cartilage in the knee joint) and most frequently injuries to the cranial cruciate ligament (the canine equivalent of the anterior cruciate ligament, ACL, in people).

Arthritis is among the most common conditions that Dr. Duerr and other veterinarians encounter. More specifically, there are two subtypes. Primary arthritis is typically tied to age-related wear and tear applied to the joints due to cartilage degradation (known as osteoarthritis). However, patients most commonly present to their veterinarian with secondary arthritis caused by the presence of underlying disease, such as elbow or hip dysplasia, or osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), in which a fragment of bone and cartilage separates from the joint.

In addition to arthritis, veterinarians also commonly treat soft tissue injuries most often related to muscle or tendon tears, damage to the menisci (cartilage in the knee joint) and most frequently injuries to the cranial cruciate ligament (the canine equivalent of the anterior cruciate ligament, ACL, in people). This fibrous band connects and stabilizes the stifle joint between the femur and tibia, preventing the former from slipping backward, and is frequently damaged, requiring medical or surgical intervention.

©2025 PLATINUM PERFORMANCE, INC./TOPLINE DESIGN

©2025 PLATINUM PERFORMANCE, INC./TOPLINE DESIGN

Canine Hindlimb Structures

A closer look at the bones, joints and soft tissue affecting most canine lamenesses.

Arthritis is among the most common conditions veterinarians encounter.

Primary arthritis is typically tied to age-related wear and tear applied to the joints due to cartilage degradation. However, patients most commonly present with secondary arthritis caused by the presence of underlying disease or osteochondritis dissecans, in which a fragment of bone and cartilage separates from the joint.

The canine elbow is a complex joint made up of three bones: the radius, ulna and humerus, which are a frequent source of lameness in a dog.

The canine elbow is a complex joint made up of three bones: the radius, ulna and humerus, which are a frequent source of lameness in a dog.

Improved Diagnostics Lead to More Effective Treatment

Small animal veterinary medicine, as in human and equine medicine, has seen a significant rise in diagnostic capabilities thanks to improved imaging that provide a view of a dog’s internal organs and structures. While trusty radiographs, or X-rays, remain the first diagnostic step for most veterinarians, more advanced imaging modalities are at the ready, and each has its own strengths in helping to diagnose conditions involving bones, joints and surrounding soft tissue structures. These modalities range from ultrasound and MRI, or magnetic resonance imaging, to computed tomography (CT), single-photon emission tomography (SPECT) and even PET, or positron emission tomography. These tools use different technologies from sound, radio and magnetic waves to radioactive tracers that create 3D images of an organ’s function. “One of the reasons why I love being at CSU is because we have so many options to diagnose in an objective way,” affirms Dr. Duerr. At the same time, and thanks to experience, veterinarians can often tell what is likely going on without using advanced imaging that comes with a high price tag and, in some cases, requires the animal to be put under general anesthesia. While imaging is available to provide more concrete answers, veterinarians frequently rely on their experience to deduce a likely diagnosis, then confirm it where appropriate with advanced imaging. “As an example, when we see joint effusion, instability, and arthritis in a patient’s stifle, 99.5% of the time that’s a cruciate (ACL or CaCL) tear,” he confirms. “We don’t jump to an MRI as they commonly would in human medicine. In these cases, we don’t always need advanced imaging. Another example would be a shoulder problem. We see a lot of soft tissue conditions within the canine shoulder. Biceps and supraspinatus tendinopathies (where the biceps brachii tendon and the supraspinatus tendon in the shoulder are affected by inflammation and degeneration, causing pain and reduced function) are quite common. In those cases, we frequently use the combination of radiographs and ultrasound. Ultrasound is fantastic because it emits no ionizing radiation and requires minimal sedation, and though it’s easy to do, it’s not easy to do well.” Veterinarians with specialized ultrasound training are often consulted to perform this for optimal results. “Combining ultrasound with radiographs usually gives us a pretty good idea of what’s going on in the shoulder in particular,” says Dr. Duerr

A case in point is the canine elbow, a complex joint made up of three bones, the radius, ulna and humerus, which are a frequent source of lameness in a dog. Veterinarians turn more frequently to CT scans for speed and the ability to detect small osteochondral fragments. With technological advancements, this imaging takes just minutes and can reveal remarkable definition. “These imaging modalities can be very effective themselves but especially when combined,” says Dr. Duerr of a multimodal approach. “If we have a forelimb lameness, we can perform a forelimb CT. We can then support that with ultrasound if we’re suspecting anything in the shoulder. Each modality has its strengths and weakness. But together they can paint a more complete picture, and we’re combining them at least 50% of the time.” Beyond CT and ultrasound, Dr. Duerr will order an MRI if he needs a more detailed look at a localized area. “MRI is fantastic, but the downside is that it’s expensive and the dog is under general anesthesia for longer,” he says

After diagnosis, Dr. Felix Duerr begins with a preventive approach, then escalates to minimally invasive treatment options and pursues more-involved choices if necessary.

After diagnosis, Dr. Felix Duerr begins with a preventive approach, then escalates to minimally invasive treatment options and pursues more-involved choices if necessary.

A Three-Step Approach to Treatment

After diagnosis, Dr. Duerr turns to what he calls a “stepwise” approach to treatment. He begins with a preventive approach, then escalates to minimally invasive treatment options and pursues more-involved choices if necessary, depending on the individual case. “I start with the things we can do to prevent injuries and arthritis formation, and that includes components such as breeding and weight management but can extend to exercise limitations while the dog is still growing as well,” he explains. “This may also include minimally invasive surgical intervention while the dog is young for cases that may include certain types of hip dysplasia, as an example.” Preventive strategies span numerous options and can be deployed to slow or curb symptoms early, rather than waiting until more serious problems arise later in the animal’s life.

“Once we are past the stage of early intervention in young dogs, we’re at the next step, which is reacting to what has already developed,” he details. “At this stage, the treatments are mostly benign, non-harmful (low risk of adverse events) and not exceedingly expensive. These are things we’re doing all the time in the clinic.” One intervention strategy Dr. Duerr uses is focused weight management. “It may sound simple, but the fact is that over 50% of the dogs we see are overweight. And that puts undue stress on their joints and soft tissue,” he stresses. “Keeping your dog at an appropriate weight is central to their longevity, and that includes proper nutritional strategies encompassing their diet and supplementation.” A key part is adding omega-3 fatty acids to the diet through high-quality supplements. These essential fatty acids have been extensively researched as a proven method to help maintain total body health and normal inflammatory pathways and to provide support for the brain, heart, skin, coat and gastrointestinal systems. Additional supplementation for targeted health issues, such as seasonal allergies, certain gastrointestinal or digestive disorders or joint discomfort, also can be considered.

Next, Dr. Duerr examines the dog’s lifestyle and activities in relation to their health and mobility needs. “An example would be a dog that loves to play Frisbee yet has elbow dysplasia,” he says. “Catching the Frisbee requires jumping, landing, twisting and turning. This probably isn’t the best activity for this dog’s condition.” The challenge then becomes balancing its orthopedic needs with quality of life. “I’m not the type of veterinarian who tells owners, ‘You’re going to have to stop your dog’s favorite activity and switch to 10-minute leash walks only.’ That would probably be the best option where the lameness is concerned, but is it sustainable for quality of life?” Instead, he suggests modifying the dog’s typical activities which, in this case, could be throwing the disc and holding the dog on a leash until the Frisbee hits the ground, then releasing the dog to fetch it. Or perhaps switching to jogging is a better option as it avoids hard landings and midair twists and turns. “We can typically always find a good balance and solution that benefits the dog while maintaining their joy,” he says.

After analyzing the patient’s nutrition, activities and exercise, Dr. Duerr turns to more aggressive intervention if needed. “These treatment options can have a greater risk of adverse events and/or can also be more expensive for the owner,” he explains. “Here, we look at the big categories, including pain medications, joint injections, prescribed physical therapy (sometimes combined with home exercises) and other modalities that can aid in rehabilitation, including Shockwave (a non-invasive, drug-free therapy that uses higher-energy sound waves), laser, acupuncture and so on.” Additionally, there are numerous and very well-established surgeries, including joint replacements for most larger joints. “Although we can certainly perform these surgical procedures, they can have a much higher complication rate, so we don’t use them as routinely as other options,” clarifies Dr. Duerr.

“As an example, take a German shepherd. They are the poster children for hip and elbow dysplasia. There are very strong breed predilections. Similarly, we know that labradors very often experience elbow dysplasia as well, in addition to shoulder OCDs. With golden retrievers, we watch for a lot of different conditions that afflict the elbows, shoulders, hips and knees. For every breed, there are telltale conditions that we know to look out for, and that helps us intervene early and plan.”

“As an example, take a German shepherd. They are the poster children for hip and elbow dysplasia. There are very strong breed predilections. Similarly, we know that labradors very often experience elbow dysplasia as well, in addition to shoulder OCDs. With golden retrievers, we watch for a lot of different conditions that afflict the elbows, shoulders, hips and knees. For every breed, there are telltale conditions that we know to look out for, and that helps us intervene early and plan.”

Preventing Joint and Soft Tissue Injuries for Comfort and Longevity

Although small animal veterinary medicine has evolved to offer numerous options to confront and combat mobility challenges, prevention is every veterinarian’s preferred first step. “I keep referring back to weight,” says Dr. Duerr. “Keeping your dog at an ideal body condition really is one of the most important things you can do to prevent these conditions and injuries.” In addition, veterinarians can help guide their clients toward preventive measures for breed-specific genetic challenges that are more likely to occur in some breeds over others. “As an example, take a German shepherd. They are the poster children for hip and elbow dysplasia,” he says. “There are very strong breed predilections. Similarly, we know that labradors very often experience elbow dysplasia as well, in addition to shoulder OCDs. With golden retrievers, we watch for a lot of different conditions that afflict the elbows, shoulders, hips and knees. For every breed, there are telltale conditions that we know to look out for, and that helps us intervene early and plan,” he says. “I always joke with our students that canine orthopedics isn’t really that hard. If you know the signalment and you know the breed, you can take a pretty successful guess as to what you’re dealing with. That German shepherd that walks in the door with a pelvic limb lameness will likely have either hip arthritis, lumbosacral disease, degenerative myelopathy, or stifle disease. So, that’s where we’ll start from a diagnostic perspective.”

In addition to breed-specific predispositions, nutrient deficiencies can also cause health conditions, affecting nearly all body systems, orthopedic disease included. Inadequate or imbalanced nutrition from underfeeding, use of home-cooked or raw diets or from improperly addressing an animal’s unique nutritional needs can all lead to deficiencies. Choosing a high-quality, nutrient-balanced diet supported with the right supplementation can provide optimal nourishment for dogs and be tailored to their individual weight management needs and activity level.

“There’s a huge translational opportunity because the dog has been shown to be a good model for people. Through these clinical trials, we can offer our dog owners new treatment options while assisting financially, and that research will hopefully translate over to humans down the line.”

— Dr. Felix Duerr, Colorado State University

All for the Dog

Dr. Duerr’s daily life in clinical practice and as an educator and researcher is his dream scenario. The university offers the very best in advanced diagnostics but also in cutting-edge technology that is propelling canine medicine to new heights. “For example, we have a gait lab where we use a pressure-sensitive walkway to measure exactly how much force the dogs are placing on each leg,” he says. “We then try to make it a little bit more objective, by performing clinical trials, measuring precisely how much a product is factually contributing to a dog’s well-being. The dogs wear activity collars that measure their daily activity, and they receive regular veterinary exams coupled with owner questionnaires. This combination of data gives us a good idea of the impact a product or therapy is having.”

Interestingly, Dr. Duerr shares that he and his research team watch out for certain factors that can affect the validity of their studies. “The caregiver placebo effect can be huge,” he says in reference to an owner’s perception of the results their dog may or may not actually be experiencing. We know the caregiver placebo effect can happen at least 50% of the time, and even more in non-randomized settings. This can include bias from the veterinarian as well as the client. We all want results, but it’s important that we objectively measure them for accuracy.”

Advancements in research are fueling improvements in not just small animal medicine, but in certain cases, for humans as well. CSU is home to the C. Wayne McIlwraith Translational Medicine Institute, a forward-pointed, state-of-the-art facility where veterinary and human medicine intersect to spur progress for pets, horses and people. “There’s a huge translational opportunity because the dog has been shown to be a good model for people. Through these clinical trials, we can offer our dog owners new treatment options while assisting financially, and that research will hopefully translate over to humans down the line,” says Dr. Duerr with obvious enthusiasm.

Dr. Felix Duerr’s veterinary journey started in Hanover, Germany, about 150 miles west of Berlin where he earned his degree followed by an internship at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada. A surgical residency and masters program brought him to Colorado State in Fort Collins, in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains, where the student became a mentor. Here, he has found his calling, relishing the daily work that has defined his career in veterinary medicine — as a clinician, researcher, educator and, perhaps most importantly, avowed dog lover. “In front of me there’s always a dog that looks at me, wags his tail and jumps up on me. How could it be better than that?” he smiles rhetorically. “This is just a fantastic job. I know I can help these owners that have such a hard time watching their dogs limp or become inactive and in pain. Being able to make a difference like that is amazing, and our hope is that through the mobility-focused research we do, we can make meaningful changes for these dogs and continuously improve the options we have available to treat them. I’m so lucky. This isn’t a job; I get paid for my passion.”